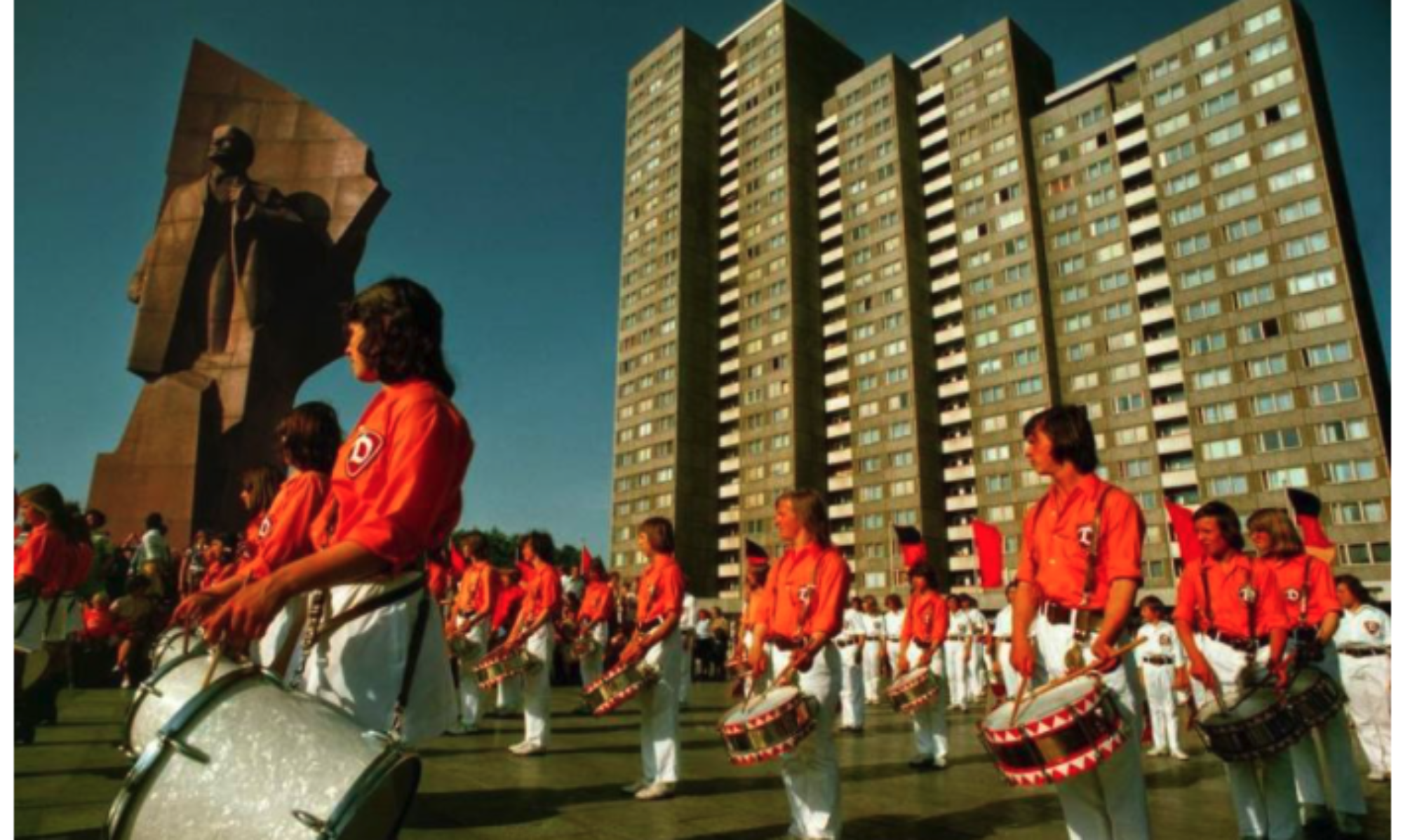

A thread of Applebaum’s book that really interested me were these prevailing and sometimes dueling senses of glorification and “sanitization” or censorship that are explored especially in the fourth chapter, with regards to all forms of media and propaganda: monuments, holidays, films, magazines, etc. The erection of statues and other monuments (and the subsequent shame and destruction of them in the post-Stalinist Czech period) was a massive undertaking, and one that capitalized on the extreme veneration of Stalin and the careful erasure of soldiers’ suffering and trauma. What, really, is the role of monuments in a historical context, especially considering the brevity of some of these statues’ lifespans? Their destruction shows the hefty erasing work on the part of the Czechoslovak government after Stalin’s influence dwindled, but this is not to commandeer the significant erasing going on during his period of reign, too. Holidays like May 9th, the “Day of the Liberation of Czechoslovakia by the Soviet Army,” worked actively to “explicitly [usurp] the role Czechoslovaks had played fighting the Nazis, and further [entrench] the Soviets’ chronology of the conflict” (86). Films ignored the brutal humanity of wartime experienced by Soviet soldiers: “combat scenes lack[ed] emotion and tension” (87). Articles published in popular Czech magazines were notorious for how they “gloss[ed] over the typical emotional and physical experiences of war: exhaustion, hunger, pain, injury, fear, and grief” (87). This rewriting of history and the massively hyperbolic heroization of Soviet loyalists is a complicated and interesting phenomenon. What was the need for this sanitization? Wouldn’t you expect people to see through the exaggerative efforts undertaken by the country and the government? Why did they feel compelled to believe and participate in this rhetoric? What do you make of the post-Stalinist experience of continuing to erase?

The Emotion & The Inspector Scenes

Kovaly’s rendering of the particular heinousness of show trials is thorough and evocative. What most interests me is the complicated ways in which she reacts to her ostracism–she experiences obvious fear, but also displays grit and anger and vulnerability and even bitter humor in some ways. Her struggle to provide basic necessities for herself and her family, her treatment by other people–especially women–in public, her unawareness of and anxiety about Rudolf’s whereabouts, her run-ins with the inspectors–all of these things intersect in such a way that really complicates the narrative about wives of show trial victims touched upon in last week’s readings, laying some really powerful empathetic groundwork. This section with the inspectors is especially rich; what do you make of this idea of agencies’ abuse of the people’s trust? How does their underlying greed undermine the system they enforce? In what ways does this specific scene unravel or reinforce Kovaly’s worldview? How does Kovaly reclaim some sense of power with her comment to Comrade Inspectress? The interaction I’m thinking of is on page 130:

“She pulled me aside and whispered ‘I’ll see to it that your car is released if you sell it to me cheap.’ It was one of my rarest pleasures of the time to give her a crushing glance and to say, very loudly, ‘But Comrade, that would be dishonest!’” (Kovaly 130).

Women, Hypocrisy, and Justification in Show Trials

Although it was a comparatively minor aspect of Feinberg’s “Telling Lies, Making Truths” chapter, I was really struck by the ways in which women in particular were treated and affected by these show trials. Horáková’s trial was met with gendered responses that differed from that of any of the men’s. As Feinberg notes, “many claimed that by advocating war, Horáková had betrayed not only her country, but her femininity, giving up any hope for mercy on the grounds of womanhood” (Feinberg 15). Why was her womanhood attacked here, especially considering the more equalizing nature of the Communist regime? Why were the wives of those on trial ostracized to the extent that they were?

I also found it peculiar how contradictory the nature of the show trials were with respect to Jewish people. At several points, the chapter examines the ways in which deeply-entrenched anti-semetic sentiments were used to villainize Jewish people and validate the confessions. However, the chapter also points out that several of the accused persons’ stories and characters were conflated with Nazism, so as to draw a parallel between Nazism and imperialism: “Their connection with Nazi brutality and violence vividly illustrated the utter lack of morality that characterized the imperialist cause” (Feinberg 13). How did this hypocrisy slide? It seems very strange that the show trials would condemn the violence inflicted upon Jewish people in camps in some cases but then turn around to ostracize and denigrate Jewish people as a whole.

My last question is broader and concerns the logical justification behind these show trials that Feinberg herself hints at, especially towards the end of this chapter: why would the SU continue to churn out show trials if their intended effect (one of empowerment) was overshadowed by the reality of the workers’ reactions (feelings that the trials undermined Communist powers)? Why bother going through the process of arresting and jailing and trying based on complete fabrication if the resulting paranoia breeds more doubt and insecurity than trust in the communist government?