Thwarting the gold medal hopes of the Soviet Union, the United States Hockey team won 4-3 to stay to compete another day in the 1980 Olympic Games. Following an early goal by the Soviets, The Americans tied their Cold War adversaries not once, but twice in the first period to begin the second period at 2-2. That period would finish with a 3-2 Soviet lead before flipping the advantage to the US with a 4-3 lead halfway through the third period. Head coach Herb Brooks, who had been cut by the 1960 US team as a player, directed the team in the closing moments. At the sound of the buzzer, the underdog Americans upset the Soviets in what truly was a “Miracle on Ice” leading them to the finals against Finland. That narrative is exciting, yes, but not entirely accurate. The Americans were certainly underdogs competing against a team that had beat them 10-3 just days before but were amateurs only in the sense that they were not playing in the National Hockey League. They were a team that held a 42-16-3 record going into the Olympic games in Lake Placid and though they had just badly lost an exhibition game to the Soviets, they were a better hockey team than one might find at a recreation rink. They were also not the first US hockey team to play the Soviets—but they were the first ones to beat them since 1960, inspiring Gerald Eskenazi of the New York Times to write that “few victories in American Olympic play have provoked such reaction comparable to tonight’s decision.”[1]

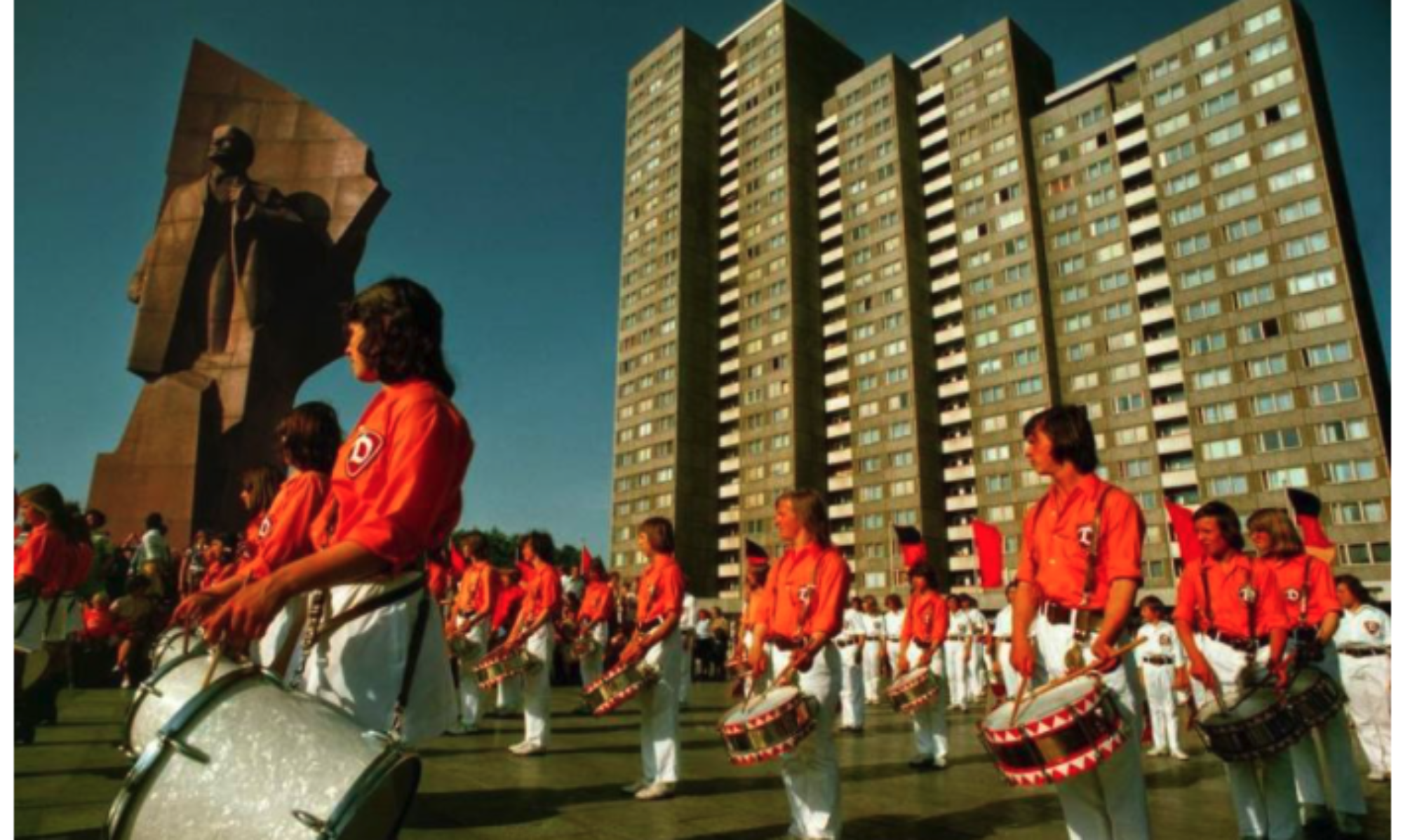

That reaction, however, came from more than just a hockey game, and that 4-3 win, of course, is not just a hockey game. The US-Soviet rivalry is one playing out on both a geo-political sphere and a hockey rink. In 1960, Dwight Eisenhower and Nikita Khrushchev were leading the United States and Soviet Union, respectively, and the Winter Olympics were in full swing. After being opened by Vice President Nixon, the American combatant in the kitchen debate, the games in Squaw Valley would see the US win gold in hockey over the regarded Canadian, Czechoslovak, and Soviet teams. Historian John Soares has argued that the Soviet team does “the bidding of the state and the party,”[2] and while “bidding” might pass a little judgement, the Soviet hockey team does indeed serve the political needs of the Communist Party. Referring to the context of the 1959 World Tournament, Soares argues “Communists touted hockey championships as evidence of the superiority of their system in generating progress.”[3] The political motives of our Communist friends should not be unfamiliar to us as Americans according to the work of MacIntosh Ross and E. K. Nagel. Regarding the last US win, they provide some context: “in 1955, the government officially involved itself in the development of soldier-athletes, passing legislation to free up talented servicemen for international competition. Although many players were civilians by 1960, it was the soldier-players of the 1950s that laid the foundation for the American Olympic victory in Squaw Valley.”[4] So while the Soviets were receiving “perks rarely available to those outside the leadership,”[5] the American military was intentionally placing soldiers on a very different kind of battlefield–one that has not seen any success in the past 20 years.

Mirroring the record of the Soviet hockey rivalry, the US has faced incredible turmoil that has taken a direct hit at the morale of this nation. The American exit from Vietnam just a few years ago, the current uncertainty of the Middle East, and of course Watergate are ever present on the American consciousness. The American sense of loss going in to the 1980 Olympics is combined with a growing discontent with foreign affairs. Historian Vladislav Zubok has written, “unfortunately for Brezhnev’s détente, the momentum for it in the United States was vanishing quickly after the Watergate scandal and the resignation of Richard Nixon in 1974.”[6] This hockey game against the Soviets is by all means political and subservient to the Cold War identities that have provided for its cultural significance. Political Scientist Donald Ableson agrees with this contextualization, stating that to the United States, the Soviet Union’s 1980 team “represented a country that had invaded Afghanistan, supplied nuclear weapons to Cuba, and tried to spread communism throughout Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Africa.”[7] It is subliminal, but the frustration with détente was fought not with guns, but with hockey sticks. Rightly so then, these events place this victory as not only a win over Soviet ideology–but also as a significant historical bright spot in this nation’s recent history. A so to speak bright spot that has the potential to catalyze this nation into a more hopeful and thriving era. For a national body still hurting from the wounds of Vietnam and the trauma of Watergate, the physical dominance displayed over the perceived hyper-masculine Soviets is a symbolic milestone. It marks the beginning of a new era in the Cold War and perhaps the eventual fall of the Soviet Union.

The American 4-3 win is not something emblematic of the Cold War—it is the Cold War. It was a competition between the dyad of world superpowers at a competition claiming, at least, to be global. There can be no cultural differentiation within a game of hockey; it is a unique display of absolutes. This game marked a decisive cultural victory for the United States in the Cold War, along with providing an important sense of hope for US citizens. Even though it is not specifically a political event, this hockey game will become a significant historical political event for the US because of the context in which it lies. It is the beginning of an era where the Cold War might be revitalized and the Soviet Union by a vote of 4-3, is not the victor.

The Miracle on Ice is among the few competitive examples between Capitalism and Communism that has taken place not only in the political arena but the athletic one as well. This is not to exclude international competition in general (i.e., The Olympics), but to directly place this hockey game in a parallel narrative with the Cold War. This game has provided an empirical outcome for the winner between these two competing ideologies. Compared to its political contemporary moments, The Miracle on Ice was not based in opinionative political conjecture but instead absolute competition. Even though detente is blooming at the time of this match, this game symbolizes all that the Cold War was and all that it has developed to be. Meaning- the outcome of this game was not just about which nation was superior in hockey, but just as much as who had won the Cold War in a broader sense. After almost 40 years of indirect global competition with the Soviets, this game was not the first, but the most prominent chance for the boys in red, white, and blue to face the Russians on that “Cold War” ice. The idea of competition between the Soviet Union and the United States is, of course, an old one. George Kennan, one of the so called “wise men”, wrote in 1946 that “the issue of Soviet-American relations is in essence a test of the overall worth of the United States as a nation among nations. To avoid destruction the United States need only measure up to its own best traditions and prove itself worthy of preservation as a great nation.”[8] In a 4-3 victory, the United States has showed a slightly arbitrary, but decisive measuring of worth. For many Americans this was not just a monumental upset in the sport of hockey alone. This win is being viewed as an icon for the championing of capitalism over communism. Hockey may seem an odd and conjectured symbol, but it is only appropriate in the throes of hammers, sickles, guns, and drums for the sake of contest.

[1] “U.S. Defeats Soviet Squad In Olympic Hockey by 4-3,” New York Times, Feb. 23, 1980.

[2] John Soares, “‘Very Correct Adversaries’: The Cold War on Ice from 1947 to the Squaw Valley Olympics,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 30, no. 13 (2013): 1539, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/1 0.1080/09523367.2013.823405.

[3] Ibid., 1537.

[4] MacIntosh Ross and E. K. Nagel, “More than a Miracle: The Korean War, Cold War Politics, and the 1960 Olympic Hockey Tournament,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 35, no. 9 (2018): 924, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0952 336 7.2018.1538130.

[5] John Soares, “‘Very Correct Adversaries’: The Cold War on Ice from 1947 to the Squaw Valley Olympics,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 30, no. 13 (2013): 1540, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/1 0.1080/09523367.2013.823405.

[6] Vladislav Zubok, “The Soviet Union and Détente of the 1970s,” Cold War History 8, no. 4, (Nov. 2008): 435, http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=10&sid=33202b46-de4e-46be-bf8a-c50d367fe7d6%40 pdc-v-sessmgr02.

[7] Donald E. Ableson, “Politics on Ice: The United States, the Soviet Union, and a Hockey Game in Lake Placid,” Canadian Review of American Studies 40, no. 1 (2010): 65, http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewe r?vid=1&sid=045232e4-f108-4f9c-a3a1-d64f00bea724%40sessionmgr103.

[8] “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” The History Guide: Lectures on Twentieth Century Europe, last modified April 13, 2012, http://www.historyguide.org/europe/kennan.html.

Bibliography

Ableson, Donald E., “Politics on Ice: The United States, the Soviet Union, and a Hockey Game

in Lake Placid,” Canadian Review of American Studies 40, no. 1 (2010): 63-94. http://ed s.b. ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewe r?vid=1&sid=045232e4-f108-4f9c-a3a1d64f 00b ea724%40sessionmgr103.

Eskenazi, Gerald. “U.S. Defeats Soviet Squad In Olympic Hockey by 4-3.” New York Times,

Feb. 23, 1980, https://www.nytimes.com/1980/02/23/archives/us-defeats-soviet-squad-in-olympic-hockey-by-43-us-six-turns-back.html.

The History Guide: Lectures on Twentieth Century Europe. “The Sources of Soviet Conduct.”

Last modified April 13, 2012. http://www.historyguide.org/europe/kennan.html.

Ross, MacIntosh and Nagel, E. K., “More than a Miracle: The Korean War, Cold War Politics,

and the 1960 Olympic Hockey Tournament,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 35, no. 9 (2018): 911-928. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0952336 7.2018.1538130.

Soares, John. “‘Very Correct Adversaries’: The Cold War on Ice from 1947 to the Squaw Valley

Olympics,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 30, no. 13 (2013): 1536-1553. https: //www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09523367.2013.823405.

Zubok, Vladislav. “The Soviet Union and Détente of the 1970s,” Cold War History 8, no. 4, (Nov. 2008): 427-447. http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=10&sid= 33202b46-de4e-46be-bf8a-c50d367fe7d6%40 pdc-v-sessmgr02.