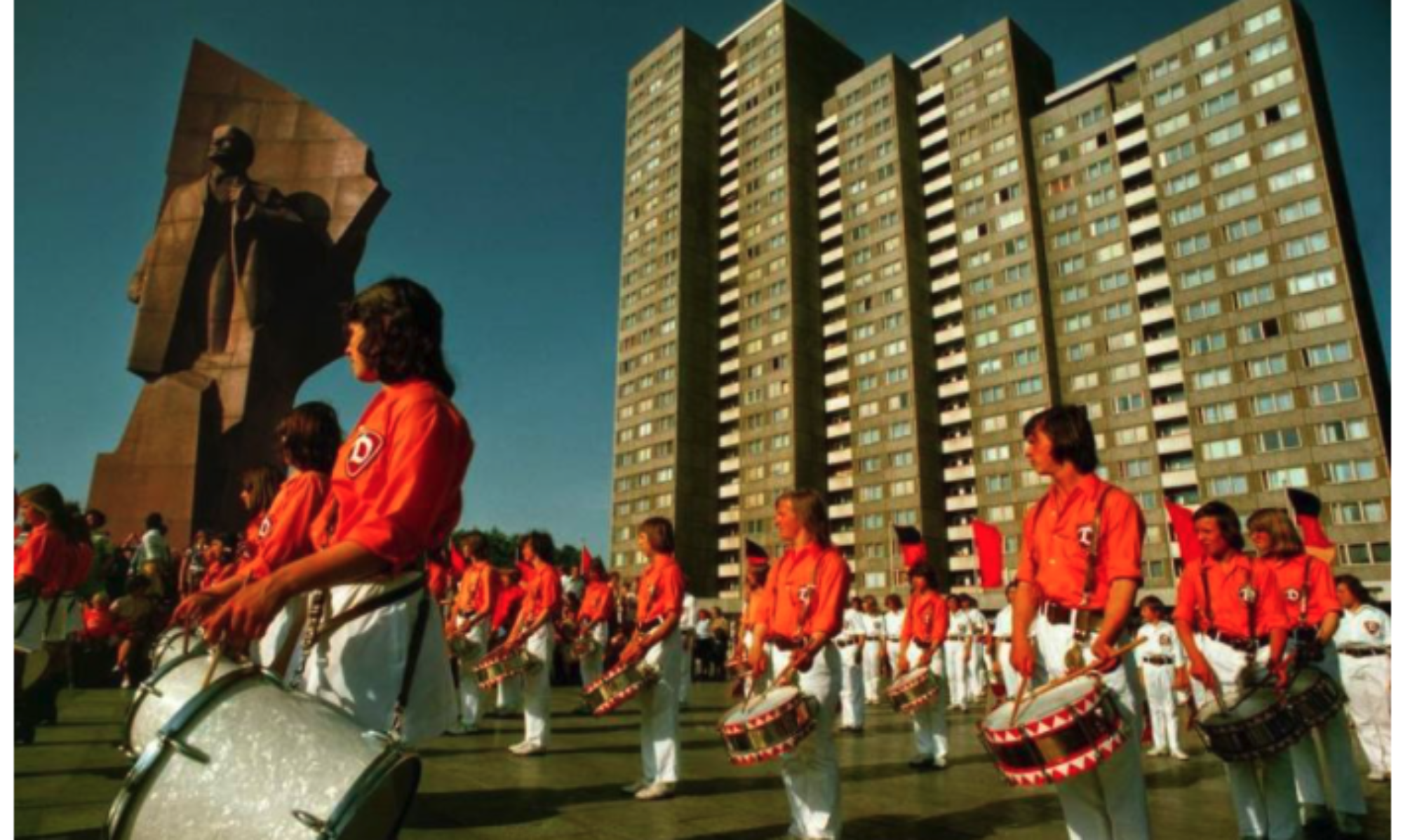

The majority of this story follows Daniel Bruhl (or as our marvel fans will know him as Helmut Zemo) trying to recreate the world of East and West Berlin a few months after the fall of the Berlin Wall. He wants to do this to protect his mother’s amnesia after she is in a coma. Now there is not really a specific quote or time that I can pull for the question that I want to ask but rather as a discussion as the movie as a whole. (However, I can point to the 01:16:00 vicinity which illustrates some of the breaking of the illusion of have the main protagonist by the erection of the Coca Cola banner and the knowledge of their father visiting the McDonalds). What I want to ask of the class then is this: how much of a parallel do what the protagonist’s actions of creating a false story/ a loaded narrative of the successes of the Socialists/Communists and the actual events we have seen with the several different countries we have studied this semester? Is what he is doing actually different from what the other countries had done, or is it similar?

“All in All, You’re Just Another Brick In The Wall”

Perhaps adding to my own naivety, or my over zealousness to synthesize events within history to draw out information or some other explanation but there was one particular line that really started to make me think. This of course, comes off the heels of the perhaps infamously is that history does not repeat itself it merely rhymes. The line that generated this line of thinking comes as follows. Garton-Ash states, “the cup of bitterness was already full to the brim. The years of Wall Sickness, the lies, the stagnation, the Soviet and Hungarian examples, the rigged elections, the police violence– all added their does. The instant that repression was lifted, the cup flowed over. And, then, with amazing speed, the East German discovered what the Poles had discovered ten years earlier, during the Pope’s visit in 1979. They discovered their solidarity. ‘Long Live the October Revolution of 1989’ proclaimed another banner on the Alexanderplatz. And, so it was: the first peaceful revolution in German history.” (Garton-Ash 69). And with this, as the title suggests, was 10 years after Pink Floyd released their 3 part song “Another Brick in the Wall.” While read had looked at the punk rock scene earlier, I feel like with this particular song, it my be interesting to look at this as well. Moreover, however, and more dealing with the quote at hand, is the notion of being brought down by a repressive imagery such as the Berlin Wall that divided a whole country, heart and soul in half for nearly 30 years. So aside from the comparison or analysis that might come from the rebellious attitudes featured in the Pink Floyd song, what type of psyche could be postulated to have been felt with the existence of the wall? Could this have been easily another one of Germany’s violent upheavals that brought with it the violent destruction and riots against the state, or, because of the Wall Sickness, was it a detestable thing that German’s had to gradual heal themselves of? Had then just put it as “another brink in their wall” and shut themselves off from the ills that it brought?

Religion Brings Peace?

I think what is particularly interesting in the one section of the reading is considering what effect religion has had within the Cold War. Largely, I do not think we have had many discussions about how religion had been downplayed in the early USSR. From the section of the manuscript, Roberts and Ash state, “The authority of the Catholic Church in Poland, already very strong, was reinforced when the archbishop of Krakow, Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, became Pope John Paul II in 1978. His philosophy and his strategic vision for the transformation of Poland can be summarized in a passage often cited by him and by Solidarity’s martyr priest, Father Jerzy Pepieluszko: ‘Be not overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.’ Towards the end of his life, John Paul II wrote, ‘If we consider the tragic scenario of violent fratricidal conflicts in different parts of the world, and the untold sufferings and injustices to which they have given rise, the only truly constructive choice is, as St. Paul proposes, to ‘abhor that which is evil and hold fast to what is good.'” (Roberts and Ash 130-131). My question to the class then, and what I think would be interesting to contemplate how religion was a catalyst for change within this society and if it were elsewhere? Was religion a driving force for why they were able to be so peaceful for so long and if so what do you think the role of religion played in other countries? Or, was it solely because of the degree to which they were religious that allowed Poland to hold these tenets and achieve these changes in the manner that they have?

The Fairness Doctrine? Soviet v. USA

The Fairness Doctrine was initiated by the FCC in the US in 1949 until 1987. The goal of these general journalistic guidelines (mainly on air rather in print) to provide equal time to controversial topics and to be “fair and balanced” when presenting them (and above all else to be honest). I mention this mainly because during this time the Soviet Reporters were subject to U.S. laws and guidelines while they were within the borders. But, I also mention it because of Khrushchev’s general hopes and aspirations. According to Fainberg, his goals were “to begin with, the press was to become a platform for coming to terms with the Stalinist past and for thinking about the future. Second, the press was expected to furnish readers with the information they needed to educate themselves and develop as socialist citizens. Finally, the press was to play a central role in the states’ efforts to mobilize citizens’ enthusiasm for building socialism, without the use of violence” (Fainberg 87). Though it is from the Soviet perspective, these two ideals (especially for Soviets in the U.S.) seem to be working against two different systems. One is pulling them to provide the most accurate (in theory) information that is possible and the other is trying to place ideology above all else. Additionally, Fainberg also states of the progression of journalism that there were questions of “were the Soviet people ready to deal with multiple perspectives and different opinions? Had the public attained the appropriate level of Marxist consciousness. These questions preoccupied the entire Soviet establishment in the wake of Khrushchev’s reforms and became the subject of much discussion in government offices and party meetings across the country” (Fainberg 94). This is a long way of getting to the essential question of what do we make of the existence of these two systems, particularly for Soviet Journalists within the U.S.? Obviously, there was a struggle and many of the Soviet Journalists were pushing for some form of reform within their own states. However, why was it so much in the mind of the Soviets about whether they were “ready” for that information or not? Is it possible that this is indicative of some form of classism (which would be ironic) or elitism? Or is this indicative that they did not trust that their “propaganda” and the state failed to adequately immerse them within the ideology? And, why should that matter?

Who you callin’ Punk? (Discussion Leader-Post)

Close to the last paragraph of the Garrard reading, she states, “The alternative culture and subcultures that already existed in the GDR were also deemed irrelevant by these young people; rock music had been co-opted by the state, and previous subcultures such as the hippie movement had lost their edge and momentum” (Garrard 176). Now, this is occurring in the 1980s, but it appears to be of some import to consider the previous decades and how this milieu of disillusionment and the subsequent losing of their edge and momentum occurred. Particularly, I would like for us to consider this quote from the Risch reading. “Published interviews indicate that young men also dominated Wroclaw hippie circles. When asked if he remembered any female hippies, Zappa said that young girls and high school students used to frequent hippie gatherings but they tended to be fans of the hippie movement rather than be active in it” (Risch 95). I mention these two quotes in conjunction to point at a possible cause of the loss of momentum in the respective movements; mainly, the notion of a “true punk” or a “true hippie” and isolation that came from within the community. For discussion (in part), to what extent do you believe that the internal structures of the movements were the product of its downfall? How much do you think these communities were unable to drum up sustained support due to patriarchal stereotypes or misogyny? Was the work of the Stasi and the State more influential in their lack of progression?

Keeping Up with the Jones’: The Russian Corollary

In Reid’s chapter in Parting the Curtain, she examines an exhibition held in Soviet territory where the U.S. was invited to present various homewares, appliances, and other sorts of articles that could be found in a “normal” American home. In preparation for this exhibition, “The Society for the Propagation of Political and Scientific Knowledge, a national lecture society, conducted conferences and seminars offering data, financial assistance, and sponsorship of lecturers. The society arranged some 10,000 lectures to anchor the propaganda counteroffensive against the exhibition” (Reid 188). Despite all these preparations for the arrival of the U.S. exhibition, “The Soviet campaign fizzled, the once highly visible agitators toned down their criticisms and increasingly gave way to teeming crowds of ordinary citizens. In fact, one U.S. diplomat reported, the remaining agitators themselves became ‘rapt with attention at U.S. displays and only hypocritically went about their tasks'” (Reid 202). What appeared to win over the crowds, by and large, with the images and wares of a new kitchen, automobiles, and clothing. The Soviet citizens were even enamored by all these things to the extent that they continuously wished to know how much things cost. With the amount of propaganda that the Soviets put into this campaign to disparage the exhibit (which they invited to their shores), they were unsuccessful in maintaining some of the illusion of the East being better off than the West. I am rather curious, however, of what others think of this seeming miscalculation. And it seems like it was a rather large miscalculation that the Soviets thought that they could win over their own citizens with just more propaganda. Why do you think that the Soviets thought that they could merely win over their citizens by using “agitators” and not a competing exhibition or by not bringing the West over at all? Should the remaining agitators continued vivaciously in their agitations would that have been successful or was there nothing the Soviets could have done to win back their citizens during this month(s)-long period? Or was the appeal of keeping up with the American “way of life” and consumerism too powerful of a motivator to keep the Soviets from trying to “keep up with the Jones.'”

Who’s Art is it Anyway

One of the most prevalent quotes of the first chapters is when the author states, “To get to ‘know’ the Soviet Union was no longer a process of discovery, comparison, and analysis as it had been during the Third Republic, but of memorization, performance, and ritual” (Applebaum 45). In fact, the Soviet Union had poured numerous hours of films and other realist art into Czechoslovakia in order to pull them into the fold of Eastern influence. The first chapter explores just how ineffective these methods were and how the entirety of this time focuses on how Czechoslovakians wished to retain their national identity. Several times Applebaum makes clear that “Brdecka also mentioned that Czechoslovak viewers were too Westernized and sophisticated to enjoy Soviet films. He claimed that Soviet films were made exclusively with the needs of Soviet audiences in mind– people who are in some regions, still very unrefined and primitive” (Applebaum 38). Applebaum even goes so far as to point out that, “By drawing on stereotypes of the unrefined earthy Russian soul… posited the USSR as a foil for a more sophisticated, Western, and modern [Czechoslovakia]…” (Applebaum 41). These quotes and others exemplify the need for Czechoslovakians to retain their national identity and become an amalgamation, a nexus really, of bother Western and Eastern ideologies. The question, I have then for discussion and to put to you, is how influential was that bombardment of propaganda? Could the Soviet Union have created (or even heeded to the criticisms of Czechoslovakians) propaganda that illustrated the USSR as refined and sophisticated? Or, do you think that ideologically (meaning through the Soviet Communistic lens) it was not possible and the Czechoslovakians were never going to be persuaded into the pure Eastern influence?

Recollecting the Past- Under a Cruel Star

A heart-breaking account of the events of the Czechoslovakian “show trials” is told though the lense of Heda Kovaly. Many of the events surrounding the Slansky show trial and the 20th Congress of the Communist Part make several appearances throughout the sections that we have read from prior readings. Echoing from those sources, Kovaly writes, “even the most casual encounter with me could arouse suspicion and invite disaster. I understand that and could bear the isolation better than most people in the same situation” (Kovaly 117). In a piece of dialogue, she writes as well that, “If the system was fair and good, it would provide ways for compensating for error. If it can only function when the leadership is made up of geniuses and all the people are [100%] honest and infallible, then it’s a bad system” (Kovaly 103-104). The one other important parallel she makes is when she states, “In Czechoslovakia, as in the Communist countries of Europe at the times of being unemployed was not merely unfortunate; it was illegal. But in a country where all the jobs had become government jobs, who would employ an outcast like myself?” (Kovaly 120). Each of these quotes echoes the themes paranoia and ostratization, of women and country turning on an individual caught up in the show trials, it even questions the efficacy of the whole governmental system. But, the question that primarily arises from these quotes is how much influence her flight into the West influence how she recollected the particulars? Certainly, much of this can be taken at face value, and that her larger picture holds some light to the events that had taken place. However, she accounts as to her and a small handful of people (immediate family members) had been caught up in these events. The majority are in fact people who are actively displacing her, following with “company policy,” and treating her poorly because of her connections to those on trial. How should we handle the divide within the nation (the Kovalys vs. the ostracizers) as historians when recreating the events of the Stalinization? Is it possible (or even should historians) attempt to sterilize the emotions of the events by present just the bare necessities, or do insights like these memoirs (equipped with time and editorial minded consumption of the material) help to better illuminate the events we had read about in the other sources we have read?

Managing Feelings: The Soviet Soap Opera known as the Show Trials

A significant portion of the article by Melissa Feinberg deals with the perceptions and the managing of perceptions of the workers and proletariat class. As she writes, “Show trials taught the audience that any pretense of amity from the West was only a mask: the forces of capitalist-imperialism were their enemy” (Feinberg 30). Dealing with the many different satellites of the Soviet bloc, Feinberg observes the effects and the different narratives that show trials took on. Ranging from antiemetic to saboteurs to the long cons, the one things that tied these trials together was the shared goal of Soviet pressure to illuminate that the “the forces of capitalist-imperialism were their enemy” and that those enemies wished to take over the countries of the Soviet sphere of influence by, “[killing] their leader, [taking] power via a coup, slowly turn the people against the USSR, and make them satellites of Yugoslavia” (Feinberg 12, 30). Playing up these fears cannot be understood with the willingness of Soviet and Communist Party leaders had in sacrificing their copatriots for the most minute notion. Perhaps highlighting their paranoia, but these show trials also demonstrate that they believed that the people around them may not have been as loyal to their cause as they had thought they might have been when they started their struggles. Especially with such sentiments underpinning the different narratives that any western influence exhibited by Yugoslavia or interactions with people of the west illustrates Communits saw that their infant economies could be thrown to the wind with the slightest disruption (Feinberg 10-11). With these fears from the upper echelons of the Communist Parties, the show trials appear to have taken on the effect of trying to manage the feelings and outward expressions of those viewing the trials.

Later in the article, however, Feinberg begins to analyze how effective these trials by suggesting “instead of considering belief as an either-or proposition, it may be more productive to think of it as falling on a spectrum and consider reactions to a trial as representing a range of responses” (Feinberg 26). After observing some of these different reactions to separate trials, she concludes, “rather than seeing this trial [Slansky’s trial] as evidence of Communist strength, some workers wondered how their leaders could have allowed the traitors to do so much damage before they were captured” (Feinberg 30). The questions that arise are multifaceted and follow as such: Is it possible that despite the evidence of support for the decisions, Feinberg presenting the conclusion of some workes being critical of them are elevated or overstated? If they are, how can that position be reconciled with the fact that many wives of the convicted were harshly ostracized (Feinberg 25-27)? Additionally, do the emotions or sentiments of the people in these cases actually matter considering that their actions illustrated support? That is to ask, does it matter that the internal dialogues of these people did not reflect their outward actions of ostracizing others, sending letters for executions, and taking on additional hours at work (Feinberg 25-27)? And lastly, were the actions that these Communist leaders took by orchestrating these show trials and the mixed reviews they received from the people detrimental to their overall goals? How did you see these trails as pushing away or pulling closer the people of these countries in a productive way? How could this opinion be contrasted, in the treatment that the USSR of their citizens and the people, with the emotions of the people of the US with trials like the Rosenbergs and other McCarthy Era arrests that targeted leftists?