I think what is particularly interesting in the one section of the reading is considering what effect religion has had within the Cold War. Largely, I do not think we have had many discussions about how religion had been downplayed in the early USSR. From the section of the manuscript, Roberts and Ash state, “The authority of the Catholic Church in Poland, already very strong, was reinforced when the archbishop of Krakow, Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, became Pope John Paul II in 1978. His philosophy and his strategic vision for the transformation of Poland can be summarized in a passage often cited by him and by Solidarity’s martyr priest, Father Jerzy Pepieluszko: ‘Be not overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.’ Towards the end of his life, John Paul II wrote, ‘If we consider the tragic scenario of violent fratricidal conflicts in different parts of the world, and the untold sufferings and injustices to which they have given rise, the only truly constructive choice is, as St. Paul proposes, to ‘abhor that which is evil and hold fast to what is good.'” (Roberts and Ash 130-131). My question to the class then, and what I think would be interesting to contemplate how religion was a catalyst for change within this society and if it were elsewhere? Was religion a driving force for why they were able to be so peaceful for so long and if so what do you think the role of religion played in other countries? Or, was it solely because of the degree to which they were religious that allowed Poland to hold these tenets and achieve these changes in the manner that they have?

Rights?

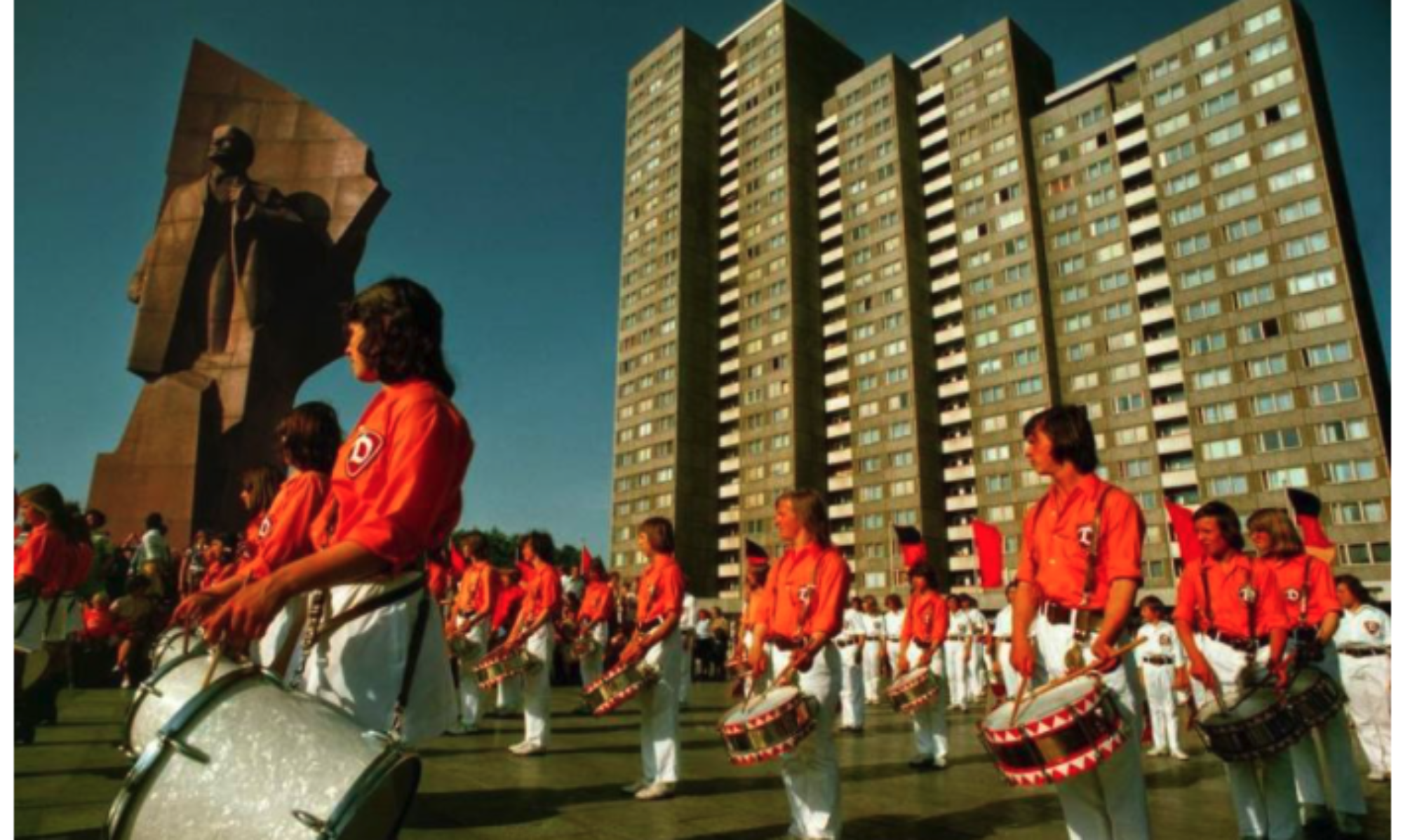

While reading “Power of the Powerless” and the chapter 4 Dictatorship and Dissent: Human Rights in East Germany in the 1970s by Ned Richardson- Little, there were a lot of similar comparisons between the two. In page 51 the author describes that those who held power in the GDR saw as human rights to be only controlled by those in power “As SED leader Walter Ulbricht said upon his return to Germany from exile, “it should look democratic, but everything must be in our hands” (Little, 51). And in Power of the powerless “Our system is most frequently characterized as a dictatorship or, more precisely, as the dictatorship of a political bureaucracy over a society which has undergone economic and social leveling” (Havel, [2]). In the beginning of Power of the powerless the author says that past history actions has caused dissent in this area. My questions to the class is, would you consider this comparison to relate what Havel was talking about? Also, do you think that by dictating what human rights is in your pov, will others see it that way? Or do you think that by restricting certain rights, no one will want it because the gov’t said so?

Human Rights and Socialism

Within the readings, the arguments surrounding human rights within the Soviet Union and, more specifically, the GDR, showed that the issues did not inherently lie with the system of socialism, but rather the ways in which the government handled such issues and its leadership. While the later periods of the Soviet Union were typically described as ones with citizens unhappy with socialism as a whole, these articles seem to prove otherwise to some extent. In the GDR, the ways that individuals used the arguments of human rights showed that they still wished to operate under the same system, but with reforms that furthered the image of the government as a whole. However, the fact that many individuals that did question or petition the government faced retribution demonstrated the fact that citizens had to operate very carefully within their countries in order to be left alone, as seen in Vaclav Havel’s narration about the grocer. Even in the advent of discussions on human rights, the people living under the Soviet Union still did not have access to basic tenets of what socialism proclaimed to guarantee them.

Havel’s account of the grocer and the propaganda sign also speaks to the fact that many people lived without thinking about the ways in which their government seeped into every element of life. Even if the grocer and customers did not pay attention to the sign, its very presence served as a reminder to behave and avoid trouble. This narrative speaks to the experience of those who were not happy, but felt that they did not have the ability to speak out, unless they should face major consequences that permeated throughout their families, businesses, and friends. The human rights movements finally gave those who did not feel that they had a voice one to advocate for them, sparking the movements that eventually led to the fall of the Berlin Wall, and major reforms within the Soviet Union.

After reading, I wonder about the true intentions of everyone involved – the government, the advocacy groups, and individuals living in the Soviet Union. Did the government truly believe that by trying to eliminate dissenters and human rights groups, the issue would be minimized or eliminated? Did the human rights groups know that their actions would heavily influence the advent of the fall of the Berlin Wall or other major events in the Soviet government? Did various individuals who petitioned to emigrate, wrote letters, and other things believe in what they wrote – that they truly enjoyed the government and its style, and their petitions were only meant to benefit the government’s efficiency?

Publication of the Helsinki Accords

In view of the more conservative leadership that was prevalent during the Brezhnev era, it makes the publication of the Helsinki Accords in Soviet media publications all the more strange and amazing. In Snyder’s book on page 55, it is stated that:

“Likely Soviet leaders thought the act’s publication would highlight its positive security measures without instigating protests. Furthermore, as the Soviet Union, and Brezhnev specifically, had long pressed for the conference, the resulting agreement, signed at a high-level international summit, was a source of pride to Soviet leaders.”

With the dismissive nature the Soviet government had so far expressed with regard to Human Rights, especially with regard to Andrei Sakharov being unable to accept his Nobel Prize because he was attending the trial of Sergei Kovalev. The actions against Yuri Orlov and other advocates in the late 1970s, who had advocated for the adoption of more Human Rights conscious policies by the Soviet government, seem to depart from what Brezhnev claimed he wanted to pursue, especially with respect to the KGB. On 73, Snyder says that the Soviet leadership, and Brezhnev himself, were hesitant to take actions against those who continued to press for reforms. It prompts several questions regarding Brezhnev’s personal motivations for these arrests. After all, did he just assume that after the Accords were printed that everything would be accepted as complete and there would be no more difficulties with reformers asking hard questions? It seems like an incredibly strange way to approach criticisms. Or, on a more cynical note, was this purely to make it easier to denounce such activists as troublemakers and prevent the actual implementation of their efforts?

Human Rights in East Germany: Can Human Rights and Dictatorship Ever Live Happily Ever After?

In chapter 4 of The Breakthrough : Human Rights in The 1970s the author discusses the front put on by the SED that seemed to quell fears in East Germany after WWII. The idea was to create propaganda or a narrative that placed a dictatorship as a necessary way to achieve human rights. However, the author quickly points out that this idea is purely just propaganda and that the SED government had no intention of having human rights be a cornerstone of the regime. The author quotes the SED leader at the time, “As SED leader Walter Ulbricht said upon his return to Germany from exile, ‘it should look democratic, but everything must be in our hands'” (Little, 51). From what Ulbricht says it is clear that the SED really only cares about having power and pushing forward their own agenda. Continually, the author goes onto talk about how the idea of human rights are not really seen in socialist literature but in liberal literature which is more so associated with capitalism. This part of the chapter led me to wonder why the SED was not pursuing actual human rights in order to keep their citizens happy? Also, it made me consider a bigger question. Can human rights and dictatorship exist at the same time? Doesn’t the nature of socialism seem to lead to human rights, or are they in fact not related?

Discussion Post

Before we dive into questions, I think it is important to begin with a little background to the Helsinki Accords as they are mentioned throughout the readings. The Helsinki Final Act is also known as the Helsinki Accords or the Helsinki Declaration. The readings refer to these differently, but for clarity, these can be used interchangeably and refer to the same document. This was the document signed at the closed meeting of the third phase of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe and as the name states, it was held in Helsinki, Finland, during July 30th through August 1st of 1975. This document signing followed two years of negotiation referred to as the Helsinki Process. All together, 35 states participated in the signing document including all then-existing European countries (excluding Albania which later signed in 1991 and Andorra) in addition to the United States and Canada. This document was a major diplomatic agreement intended to improve the détente between the Soviet bloc and the West, but the document was not binding and lacked treaty status. Ultimately, this was an agreement to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms as well as to have cooperation in in economic, scientific, humanitarian, and other areas.

(I obviously came up with way too many discussion questions and we most definitely will not get to all of them, but I figured I would post them all now and narrow it down later based on blog posts and the discussion in class tomorrow.)

Questions about Ned Richardson-Little’s article on East Germany:

- How do we see human rights look different under socialism, where the population as a whole, rather than the autonomy of the individual, is the priority?

- For clarity: Basically, what are socialist human rights and what differences and similarities can we see compared to human rights under capitalism? Were there ways that the definition of socialist human rights fulfilled our personal meaning of human rights that capitalist human rights do not?

- Why do you think human rights aren’t mentioned by the founders of socialism like Marx and Lenin?

- With the creation of the GDR Committee for Human Rights and the tripling of its budget from 1961 to 1962, I want us to consider why this was so important for the GDR. When considering the Soviet Union, we know that there is an overall hesitancy to spend money unnecessarily or raise budgets in any way, so what was at stake for the GDR that caused them to start taking this issue of human rights so seriously?

- In what ways were citizens of the GDR able demand change from the state given this new focus on human rights and international human rights norms?

- For clarity: I would like to consider here what the people wanted in the GDR and the way they used this growing focus and concern of the GDR to promote their own self-interests.

- Where do you stand on the author’s argument? Were the Helsinki Accords the most crucial turning point or breakthrough for human rights, or do you agree with the author’s stance that the turning point was actually in the 1980s?

- Follow-up: If the Helsinki Accords weren’t the turning point, what was the turning point for human rights in the GDR?

- How do we see the shift from the call for human rights in the 1970s in the GDR to the call for human rights in the 1980s – what, if anything, stayed the same and what changed?

Questions about Snyder’s article on Helsinki Monitoring in the Soviet Union - Snyder argues that the true birth of the civil rights movement occurred before the Helsinki Accords, whereas Richardson-Little argues that the real turning point was after. Which author’s argument do you support, and why?

- Consider the miscalculation of Brezhnev and other Soviet leaders when allowing the Helsinki Accords to be published. Given Brezhnev’s conservative policies in journalism that we have previously discussed, why did he allow the Helsinki accords to be published, what did they expect to happen, and why was their expectation not possible?

- Consider the Moscow Helsinki Group. How were they able to bring together such a diverse set of individuals with diverse interests and what allowed them to become such a household name?

- Snyder notes on pg. 72 that the KGB hesitated to crackdown on the Moscow Helsinki Group immediately, and there are multiple theories as to why. What is your theory as to why the KGB hesitated?

- How was this group of dissidents in Moscow able to spark a wider movement?

Questions about Havel’s speech, “The Power of the Powerless” - What do you think about the author’s discussion of the use of the word “dictatorship”? Is this a fair description, or like the Havel, do you think that it obscures the nature of power in this socialist system?

- How do you consider Havel continuing to use the word dictatorship (“even though our dictatorship has long since…”) after characterizing it in this way as obscuring the nature of power, rather than clarifying it? Was this intentional or unintentional? Was this to provide clarity due to its frequent use, or is there a part of Havel that agrees that this is a dictatorship?

- Havel gives the example of the greengrocer, stating that the greengrocer does not believe in the message of the poster in his shop window and that people who pass by do not read the message in his shop window. Do you think this is generally the case in the Soviet Union and Eastern bloc, or is this dismissive of the power of propaganda and ideology?

- To put it more generally, what do you think about Havel’s argument against Soviet ideology and propaganda? Are you buying it?

Propaganda

We see in Havel’s piece, “Power of the Powerless”, that he has some extreme opinions on the blatant propaganda of the Soviet Union. His example lies in that of a greengrocer, who puts a sign up in his shop window that says “Workers of the world unite!”. Havel argues that this sign is not there to rally his fellow citizens, or to show his support to the Soviet Union, but rather out of fear. The grocer, in this example, is afraid of what would happen if he didn’t put on such a public display of loyalty to the Union. Havel argues that this is the reason why many people at the time had such blatant pieces of propaganda all around them.

It is interesting to see this happening in the Soviet Union – though not surprising. However, I am curious to see if anyone thinks there was a similar fear in the United States? We do not have exact evidence in these papers, but from what we have learned in this class, we may be able to answer that question.

A Miner’s Memoir Turned Teachable Moment?

Within chapter 5 of Fainberg’s book, she discusses how Soviet journalists were able to tell readers of the common issues within the United States through the stories of individuals that lived it. The miner’s story reflected the themes of poverty, non-empathetic business, and the individual’s attempts to hold on to a past that could never be revived. By doing so, one could not detach the disparity of such stories from the “American dream.” Additionally, the towns that these issues took place in were usually tucked away in the Appalachian mountains among impoverished areas that all shared similar fates, which brought these articles to light not only to Soviet readers, but also perhaps to American audiences as well. When the people are not able to share their stories themselves because of inaccessibility, these Soviet reporters were able to expose them, while also taking advantage of the opportunity in order to show the American disparities.

I wonder then, if these stories written by Soviet journalists then also exposed them to American readers, if they were accessible or translated later? As Fainberg wrote, many American officials that read Soviet pieces saw them as positioned to bolster the Soviet government’s ideology, but did they see the issues brought forth as well? Fainberg’s example of the Smoky the Bear correlation shows that they understood the issues, but was it only after Soviet writing did they become apparent?