Garton-Ash’s firsthand account of the Wall raised interesting discussion of the impact the Wall had on the people of East German people. Before the collapse of the Wall, an East Berlin doctor described the phenomenon of “The Wall Sickness” (Garton-Ash, 65). This refers to the concept that the Wall placed unique psychological burdens on the people of East Germany unlike what occurred in any other East European countries. As a result of this “Wall Sickness” real sicknesses and suicides resulted.

Ultimately, this phenomenon is very real – psychological stress can cause physical conditions. In 2019, a University of Queensland research collaboration found that people living in countries that have experienced armed conflict are five times more likely to develop anxiety or depression. As we know, East Germany emerged from WW2 only to experience occupation by the Soviet Union and armed control by the Stasi. Though the East German doctor referred to this as “Wall Sickness” – and it certainly was related to the wall – this phenomenon is unfortunately not entirely unique and it is one that we have names for.

Another situation discussed with psychological background surrounds the people who chose not to emigrate. Baerbel Bohley stated “I don’t want to say these forty years have just been wasted, because in that case I might as well have left twenty years ago” (Garton-Ash, 74). To put it simply, it is hard to change our own minds. And it is hard, or even harder, to admit that we made the wrong decision. In order to grapple with that internal conflict (known as cognitive dissonance), it is easier to cling to our views and decisions after they are formed. For Bohley, that decision was made over twenty years ago by not fleeing from the East. Combined with the fact that Bohley leaving would mean moving away from everything that is known and comfortable, it is easier for the mind to stay. As Garton-Ash asks “Were they now at once to concede that it had all been in vain?” As we see with Bohley and other who remained in the East, many were not.

What other psychological implications do we see from the existence of and the fall of the Wall? Do we see these occurring anywhere else in the Eastern Bloc or Soviet Union? With the current discussion we are having as a society on mental health, how can we consider the toll these events had on people?

I definitely think that a lot of the events happening around the fall of the Berlin Wall and the late years of the Soviet Union’s existence depended on psychological hold and the deterioration of that hold on the people. As Levesque wrote, no one imagined the tolerance that Gorbachev had for the changes within various Eastern European countries, which then emboldened reformers to take their chance. The fact that the Soviet Union had held such strong power for decades put the people in a position to accept and be wary of change, which is similar to the example found within East Germany. As Garton-Ash wrote, many people remained skeptical until they were absolutely certain they would not face punishment from the Stasi for crossing between either side of Germany. I think as a whole, the citizens throughout Eastern Europe had been conditioned to the existence of the Cold War, and the opportunity to change the playing field contributed to the massive wave of reform and demonstrations. Many people had lost or denied themselves hope for change, and implicates major psychological conditioning; the tolerance of Gorbachev then caused a spark that no one could then put out. The various responses within the Eastern European countries also confirms that the cultural psyche of the nation directly manifested in how they changed their governments.

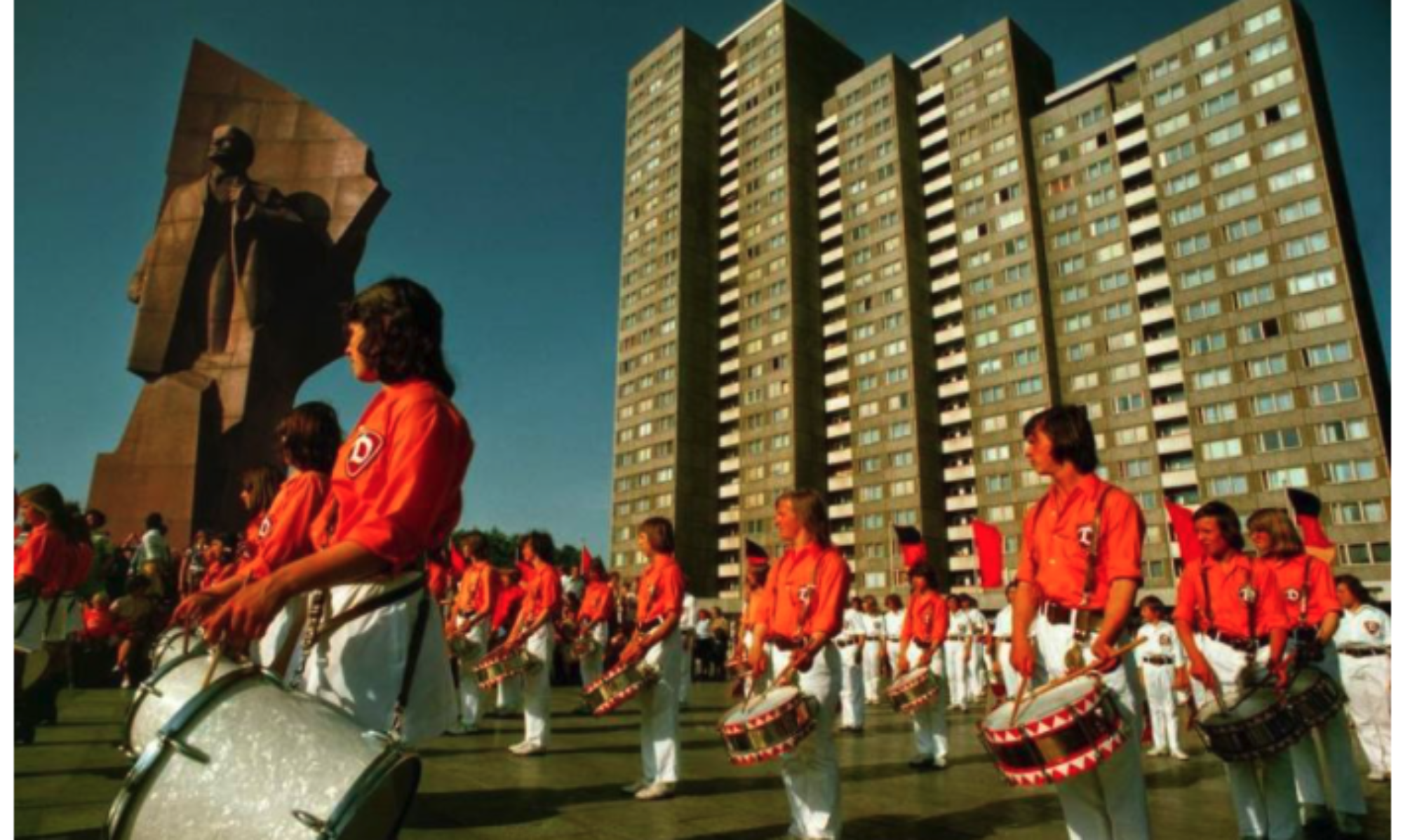

That question reminds me of Foucault and his ideas of surveillance; “surveillance is permanent in its effects, even if it is discontinuous in its action.” At the moment of the wall coming down and its immediate aftermath, Germans, particularly East Germans had to conceptualize reality from the imagined condition created by the GDR. The wall was down and Gorbachev had every intention of keeping it that way but who was actually to know that?

I think Fon’s point that the collective condition of each country who experienced some sort of revolution contributed to the type of revolution they had is really important. I think we have to remember that each case study is full of a unique people with unique histories and traumas.

The separation of Germany into two states also has to have lasting ramifications that clearly live on economically but the idea of separate Germanys has to play into the identity of those who had lived there or currently do. The culture between East and West had to live in Germany and even though reunification was immensely popular, those distinctions still exist.